KYKLOPES

Greek Name

Κυκλωψ Κυκλωπες

Transliteration

Kyklôps, Kyklôpes

Latin Spelling

Cyclops, Cyclopes

Translation

Orb-Eyed (kyklos, ops)

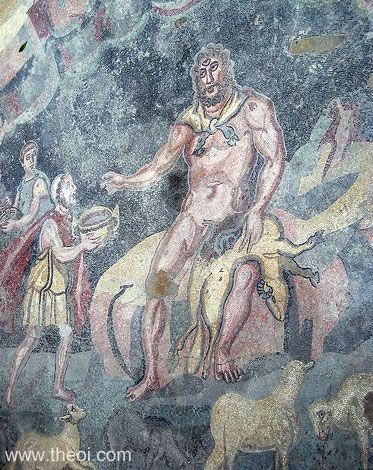

THE YOUNGER KYKLOPES (Cyclopes) were a tribe of primitive, one-eyed giants who dwelt in caves and herded flocks of sheep on the island of Hypereia (which was later identified by the Greeks with Sicily).

The Hypereian Kyklopes were closely related to the Gigantes and Phaiakians (Phaeacians) both of which were born from the blood of the castrated Ouranos (Uranus) spilt upon the earth.

The first of these giants, in both strength and stature, was Polyphemos. Unlike the rest of the tribe he was a son of the god Poseidon.

The three elder Kyklopes (Cyclopes) were a different breed altogether. These ancient beings fought with Zeus in the Titan-War and forged the weapons of the gods. Nevertheless they were also sometimes located on the island of Sicily.

FAMILY OF THE CYCLOPES

PARENTS

Probably GAIA & the blood of OURANOS *

* In the Odyssey Homer says they were closely related to the Gigantes and the Phaiakes (Phaeacians ) both of which were born of Gaia (the Earth) when she was impregnated by the blood of the castrated Ouranos (the Sky).

ENCYCLOPEDIA

CYCLO′PES (Kuklôpes), that is, creatures with round or circular eyes. In the Homeric poems the Cyclopes are a gigantic, insolent, and lawless race of shepherds, who lived in the south-western part of Sicily, and devoured human beings. They neglected agriculture, and the fruits of the field were reaped by them without labour. They had no laws or political institutions, and each lived with his wives and children in a cave of a mountain, and ruled over them with arbitrary power. (Hom. Od. vi. 5, ix. 106, &c., 190, &c., 240, &c., x. 200.) Homer does not distinctly state that all of the Cyclopes were one-eyed, but Polyphemus, the principal among them, is described as having only one eye on his forehead. (Od. i. 69, ix. 383, &c.) The Homeric Cyclopes are no longer the servants of Zeus, but they disregard him. (Od. ix. 275; comp. Virg. Aen. vi. 636 ; Callim. Hymn. in Dian. 53.)

Source: Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.

CLASSICAL LITERATURE QUOTES

Homer, Odyssey 7. 200 ff (trans. Shewring) (Greek epic C8th B.C.) :

"[King Alkinoos (Alcinous) of the Phaiekes (Phaeacians) addresses his people :] ‘In the past they

[the gods] have always appeared undisguised among us at our offering of noble hecatombs; they have feasted

beside us, they have sat at the same table. And if one of us comes upon them as he travels alone, then too they

have never as yet made concealment, because we are close of kin (egguthen) to themselves, just like

those of the Kyklopes (Cyclopes) race or the savage people (phyla) of the Gigantes

(Giants).’"

[N.B. It is not clear exactly why Homer describes these three races as "close of kin." Later classical

writers, however, explain this passage by saying that the Gigante, Phaeacian--and presumably Kyklops--tribes

were born of the Earth when she was impregnated by the blood of the castrated sky-god Ouranos. Cf. Apollonius

Rhodius 4.982 on the sickle of Kronos (Cronus).]

Homer, Odyssey 6. 3 ff :

"The Phaiakes (Phaiacians); these were a people that in times past had inhabited spacious Hypereia near the

masterful Kyklopes (Cyclopes) race, who were stronger than they and plundered them continually. So king

Nausithous the Phaiakes transplanted his people from Hypereia and settled them in Skheria (Scheria)."

Homer, Odyssey 9. 110 ff (trans. Shewring) (Greek epic C8th B.C.) :

"[Odysseus describes his encounter with the Kyklopes (Cyclopes) :] We came to the land of the Kyklopes

(Cyclopes) race, arrogant lawless beings who leave their livelihoods to the deathless gods and never use their

own hands to sow or plough; yet with no sowing and no ploughing, the crops all grow for them--wheat and barley

and grapes that yield wine from ample clusters, swelled by the showers of Zeus. They have no assemblies to

debate in, they have no ancestral ordinances; they live in arching caves on the tops of high hills, and the head

of each family heeds no other, but makes his own ordinances for wife and children.

Outside the harbour of the country, neither very near it nor very far from it, there is a small well-wooded isle

. . . it remains unploughed and unsown perpetually, empty of men, only a home for bleating goats. For the

Kyklopes nation possess no red-prowed ships; they have no ship-wrights in their country to build sound vessels

to serve their needs, to visit foreign towns and townsfolk as men elsewhere do in their voyages."

Homer, Odyssey 9.187 - 542 :

"[Odysseus describes his encounter with the Kyklopes (Cyclopes) :] Then we began to turn our glances to the

land of the Kyklopes tribe nearby; we could see smoke and hear voices and the bleating of sheep and goats . . .

When we reached the stretch of land I spoke of--it was not far away--there on the shore beside the sea we saw a

high cave overarched with bay-trees; in this flocks of sheep and goats were housed at night, and round its mouth

had been made a courtyard with high walls of quarried stone and with tall pines and towering oaks. Here was the

sleeping-place of a giant who used to pasture his flocks far afield, alone; it was not his way to visit the

others of his tribe; he kept aloof, and his mind was set on unrighteousness. A monstrous ogre, unlike a man who

had ever tasted bread, he resembled rather some shaggy peak in a mountain-range, standing out clear, away from

the rest.

Most of my men I ordered to stay by the ship and guard it, but I chose out twelve, the bravest, and sallied

forth . . . I had forebodings that the stranger who might face us now would wear brute strength like a garment

round him, a savage whose heart had little knowledge of just laws or of ordinances.

We came to the cavern soon enough, but we did not find him there himself; he was out on his pasture-land,

tending his fat sheep and goats. We went in and looked round at everything. There were flat baskets laden with

cheeses; there were pens filled with lambs and kids, though these were divided among themselves--here the

firstlings, then the later-born, and the youngest of all apart again. Then, too, there were well-made

dairy-vessels, large and small pails, swimming with whey . . . I was eager to see the cavern's master and hoped

he would offer me the gifts of a guest, though as things fell out, it was no kind host that my comrades were to

meet.

Then we lit a fire, and laying hands on some of the cheeses we first offered the gods their portion, then ate

our own and sat in the cavern waiting for the owner. At length he returned, guiding his flocks and carrying with

him a stout bundle of dry firewood to burn at supper. This, with a crash, he threw down inside, and we in dismay

shrank hastily back into a corner. Next, he drove part of his flocks inside--the milking ewes and milking

goats--but left the rams and he-goats outside in the fenced yard. Then to fill the doorway he heaved up a huge

heavy stone; two-and-twenty good four-wheeled wagons could not shift such a boulder from the ground, but the

Kyklops (Cyclops) did, and fitted it in its place--a massive towering piece of rock. Then he sat down and began

to milk the ewes and the bleating goats, all in due order, and he put the young ones to their mothers. Half the

milk he now curdled, gathered the curd and laid it in plaited baskets. The other half he left standing in the

vessels, meaning to take and drink it at his supper. Having quickly despatched these tasks of his, he rekindled

the fire and spied ourselves.

He asked us : ‘Strangers, who are you? What land did you sail from, over the watery paths? Are you bound

on some trading errand, or are you random adventurers, roving the seas as pirates do, hazarding life and limb

and bringing havoc on men of another stock?’

So he spoke, and our hearts all sank; his thundering voice and his monstrous presence cowed us. But I plucked up

courage enough to answer : ‘We are Akhaians (Achaeans); we sailed from Troy and were bound for home . . .

We have reached your presence, have come to your knees in supplication, to receive, we hope, your friendly

favour, to receive perhaps some such present as custom expects from host to guest. Sir, I beg you to reverence

the gods. We are suppliants, and Zeus himself is the champion of suppliants and of guests; god of guests is a

name of his; guests are august, and Zeus goes with them.’

So I spoke. He answered at once and ruthlessly : ‘Stranger, you must be a fool or have come from far

afield if you tell me to fear the gods or beware of them. We of the Kyklopes race care nothing for Zeus and for

his aegis; we care for none of the gods in heaven, being much stronger ourselves than they are. Dread of the

enmity of Zeus would never move me to spare either you or the comrades with you, if I had no mind to it myself.

But tell me a thing I wish to know. When you came here, where did you moor your ship? Was it at some far point

of the shore or was it near here?’

So he spoke to me, feeling his way, but I knew the world and guessed what he was about. So I countered him with

crafty words : ‘My ship was shattered by Poseidon . . .’

To these words of mine the savage creature made no response he only sprang up, and stretching his hands towards

my companions clutched two at once and battered them on the floor like puppies; their brains gushed out and

soaked the ground. Then tearing them limb form limb he made his supper of them. He began to eat like a mountain

lion, leaving nothing, devouring flesh and entrails and bones and marrow, while we in our tears and helplessness

looked on at these monstrous doings and held up imploring hands to Zeus.

But when the Kyklops (Cyclops) had filled his great belly with the human flesh that he had devoured and the raw

milk he washed it down with he laid himself on the cavern floor with his limbs stretched out among his beasts.

Then with courage rising I thought at first to go up to him, to draw the keen sword from my side and stab him in

the chest, feeling with my hand for the spot where the midriff enfolds the liver; but second thoughts held me

back, because we too should have perished irremediable; never could we with all our hands have pushed away from

the lofty doorway the massy stone he had planted there. So with sighs and groans we awaited ethereal Dawn.

Dawn comes early, with rosy fingers. When she appeared, the Kyklops rekindled the fire, milked his beasts in

accustomed order and put the young ones to their mothers. Having quickly despatched these tasks of his, he

clutched another two of my comrades and made his breakfast of them. This over, he drove his flocks out of the

cave again, easily moving the massy stone and then putting it back once more as one might put the lid back on a

quiver. Whistling loud, he led off his flock to the mountain-side; so I was left there to brood mischief,

wondering if I might take vengeance on him and if Athene might grant me glory.

After all my thinking, the plan that seemed best was this. Next to the sheep-pen the Kyklops had left a great

cudgel of undried olive-wood, wrenched from the tree to carry with him when it was seasoned. As we looked at it,

it seemed huge enough to be the mast of some great dark merchant-ship with its twenty oars . . . so long and so

thick it loomed before us. I stood over this, and myself and cut off six feet of it; then I laid it in front of

my companions and told them to make it smooth; smooth they made it, and again I stood over it and sharpened it

to a point, then took it at once and put it in the fierce fire to harden. Then I laid it in a place of safety;

there was dung in layers all down the great cave, and I hid the stake under this. I asked the men to cast lots

for joining me--who would help me to lift the stake and plunge it into the giant's eye as soon as slumber stole

upon him? The men that the lots fell upon were the very ones I should have chosen--four of them, and I made a

fifth.

Towards nightfall the Kyklops came home again, bringing his fleecy flocks with him. He drove all the beasts into

the cave forthwith, leaving none outside in the fenced courtyard--had he some foreboding, or was it a god who

directed him? He lifted the massy door-stone and put it in place again; he sat down and began to milk the sheep

and the bleating goats, all in accustomed order, and he put the young ones to their mothers. Having quickly

despatched these tasks of his, he clutched another two of my comrades and made his meal of them. And at that I

came close to the Kyklops and spoke to him, while in my hands I held up an ivy-bowl brimmed with dark wine :

‘Kyklops, look! You have had your fill of man's flesh. Now drain this bowl and judge what wine our ship

had in it. I was bringing it for yourself as a libation, hoping you would take pity on me and would help to send

me home. But your wild folly is past all bounds. Merciless one, who of all men in all the world will choose to

visit you after this? In what you have done you defy whatever is good and right.’

Such were my words. He took my present and drank it off and was mightily pleased with wine so fragrant. Then he

asked for a second bowlful of it : ‘Give me more in your courtesy and tell me your name here and now--I

wish to offer you as my guest a special favour that will delight you. Earth is bounteous, and for my people too

it brings forth grapes that thrive on the rain of Zeus and that make good wine, but this is distilled from

nectar and ambrosia.’

So he spoke, and again I offered the glowing wine; three times I walked up to him with it; three times he

witlessly drank it off. When the wine had coiled its way round his understanding, I spoke to him in

meek-sounding words : ‘Kyklops, you ask what name I boast of. I will tell you, and then you must grant me

as your guest the favour that you have promised me. My name is Noman; Noman is what my mother and father call

me; so likewise do all my friends.’

To these words of mine the savage creature made quick response : ‘Noman that one shall come last among

those I eat; his friends I will eat first; this is to be my favour to you.’

With these words he sank down on the floor, then lay on his back with his heavy neck drooping sideways, till

sleep the all-conquering overcame him; wine and gobbets of human flesh gushed from his throat as he belched them

forth in drunken stupor. Then I drove our stake down into the heap of embers to get red-hot; meanwhile I spoke

words of courage to all my comrades, so that none of them should lose heart and shrink from the task. But when

the stake, green though it was, was about to catch fire and glowed frighteningly, I drew it towards me out of

the fire, while the others took their stand around me. Some god breathed high courage into us. My men took over

the keen-pointed olive stake and thrust it into the giant's eye; I myself leaned heavily over from above and

twirled the stake round . . . We grasped the stake with its fiery tip and whirled it round in the giant's eye.

The blood came gushing out round the red-hot wood; the heat singed eyebrow and eyelid, the eyeball was burned

out and the roots of the eye hissed in the fire . . . His eye hissed now with the olive-stake penetrating it. He

gave a great hideous roar; the cave re-echoed, and in terror we rushed away. He pulled the blood-stained stake

from his eye and with frantic arms tossed it away from him.

Then he shouted loud to he Kyklopes kinsmen who lived around him in their caverns among the windy hill-tops.

Hearing his cries they hastened towards him from every quarter, stood round his cavern and asked him what ailed

him : ‘Polyphemos, what dire affliction has come upon you to make you profane the night with clamour and

rob us of our slumbers? Is some human creature driving away your flocks in defiance of you? Is someone

threatening death to yourself by craft of by violence?’

From inside the cave the giant answered : ‘Friends, it is Noman's craft and no violence that is

threatening death to me.’

Swiftly their words were borne back to him : ‘If no man is doing you violence--if you are alone--then this

is a malady sent by almighty Zeus from which there is no escape; you had best say a prayer to your father, Lord

Poseidon.’

With these words they left him again, while my own heart laughed within me to think how the name I gave and my

ready with had snared him. Racked with anguish, lamenting loudly, the Kyklops groped for the great stone and

pushed it from the door-way, then in the doorway he seated himself with outstretched hands, hoping to seize on

some of us passing into the open among the sheep--so witless did he take me to be . . . There were big handsome

rams there, well-fed, thick-fleeced and with dark wool. Making no noise, I began fastening them together with

plaited withies, the same that the lawless monstrous ogre slept on. I took the rams three by three; each middle

one carried a man, while the other two walked either side and safeguarded my companions; so there were three

beats to each man. As for myself--there was one ram that was finest of all the flock; I seized his back, I

curled myself up under his shaggy belly, and there I clung in the rich soft wool, face upwards, desperately

holding on and on. In this dismal fashion we waited now for ethereal Dawn.

Dawn comes early, with rosy fingers. When she appeared, the rams began running out to pasture, while the

unmilked ewes around the pens kept bleating with udders full to bursting. Their master, consumed with hideous

pains, felt along the backs of all the rams as they stood still in front of him. The witless giant never found

out that men were tied under the fleecy creatures' bellies. Last of them all came my own ram on his way out,

burdened both with his own thick wool and with me the schemer. Polyphemos felt him over too and began to talk to

him : ‘You that I love best, why are you last of all the flock to come out through the cavern's mouth?

Never till now have you come behind the rest: before them all you have marched with stately strides ahead to

crop the delicate meadow-flowers, before them all you have reached the rippling streams, before them all you

have shown your will to return homewards in the evening; yet now you come last. You are grieving, surely, over

your master's eye, which malicious Noman quite put out, with his evil friends, after overmastering my wits with

wine; but I swear he has still not escaped destruction. If only your thoughts were like my own, if only you had

the gift of words to tell me where he is hiding from my fury! Then he would be hurled to the ground and his

brains dashed hither and thither across the cave; then my heart would find some relief from the tribulations he

has brought me, unmanly Noman!’

So speaking, he let the ram go free outside. As for ourselves, once we had passed a little way beyond cave and

courtyard, I first loosed my own hold beneath the ram, then I untied my comrades also. We herded the many sheep

in haste--fat plump creatures with long shanks--and drove them on till we reached our vessel . . .

But when we were no further away [out at sea] than a man's voice, I called to the Kyklopes and taunted him :

‘Kyklops, your prisoner after all was to prove not quite defenceless--the man whose friends you devoured

so brutally in your cave. No, your sins were to find you out. You felt no shame to devour your guests in your

own home; hence the requital from Zeus and the other gods.’

Rage rose up in him at my words. He wrenched away the top of a towering crag and hurled it in front of our

dark-prowed ship. The sea surged up as the rock fell into it; the swell from beyond came washing back at once

and the wave carried the ship landwards and drove it towards the strand. But I myself seized a long pole and

pushed the ship out and away again, moving my head and signing to my companions urgently to pull at their oars

and escape destruction; so they threw themselves forward and rowed hard. But when we were twice as far out on

the water as before, I made ready to hail the Kyklops again, though my friends around me, this side and that,

used all persuasion to restrain me : ‘Headstrong man, why need you provoke this savage further? The stone

he threw out to sea just now dashed the ship back to the shore again, and we thought we were dead men already.

Had he heard any sound, any words from us, he would have hurled yet another jagged rock and shattered our heads

and the boat's timbers, so vast his reach is.’

So they spoke, but my heart was proud and would not be gain-said; I called out again with rage still rankling :

‘Kyklops, if anyone among mortal men should ask who put out your eye in this ugly fashion, say that the

one who blinded you was Odysseus the city-sacker, son of Laertes and dweller in Ithaka (Ithaca).’

So I spoke. He groaned aloud as he answered me : ‘Ah, it comes home to me at last, that oracle uttered

long ago. We once had a prophet in our country, a truly great man called Telemos son of Eurymos, skilled in

divining, living among the Kyklopes race as an aged seer. He told me all this as a thing that would later come

to pass--that I was to lose my sight at the hands of one Odysseus. But I always thought that the man who came

would be tall and handsome, visibly clothed with heroic strength; instead, it has been a puny and strengthless

and despicable man who had taken my sight away from me after overpowering me with wine. But come, Odysseus,

return to me; let me set before you the presents that befit a guest, and appeal to the mighty Earthshaker to

speed you upon your way, because I am his son, and he declares himself my father. And he alone will heal me, if

so he pleases--no other will, of the blessed gods or of mortal men.’

So he spoke, but I answered thus : ‘Would that I were assured as firmly that I could rob you of life and

being and send you down to Hades' house as I am assured that no one shall heal that eye of yours, not the

Earthshaker himself.’

So I spoke, and forthwith he prayed to Lord Poseidon, stretching out his hands to the starry sky :

‘Poseidon the raven-haired, Earth-Enfolder: if indeed I am your son, if indeed you declare yourself my

father, grant that Odysseys the city-sacker may never return home again; or if he is fated to see his kith and

kin and so reach his high-roofed house and his own country, let him come late and come in misery, after the loss

of all his comrades, and carried upon an alien ship; and in his own house let him find mischief.’

This was his prayer, and the raven-haired god heeded it. Then the Kyklops lifted up a stone (it was much larger

than the first); he whirled it and flung it, putting vast strength into the throw; the stone came down a little

astern of the dark-prowed vessel, just short of the tip of the steering-oar. The sea surged up as the stone fell

into it, but the wave carried the ship forward and drove it on to the shore beyond."

Homer, Odyssey 1. 68 ff :

"Poseidon the Earth-Sustainer is stubborn still in his anger against Odysseus because of his blinding of

Polyphemos, the Kyklops (Cyclops) whose power is greatest among the Kyklopes (Cyclopes) race and whose ancestry

is more than human; his mother was the nymph Thoosa, child of Phorkys (Phorcys) the lord of the barren sea, and

she lay with Poseidon within her arching caverns. Ever since that blinding Poseidon has been against

Odysseus."

Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca E7. 3 - 9 (trans. Aldrich) (Greek mythographer C2nd

A.D.) :

"He [Odysseus] then sailed for the land of the Kyklopes (Cyclopes), and put to shore.

He left the other ships at the neighbouring island, took one in to the land of the Kyklopes, and went ashore

with twelve companions.

Not far from the sea was a cave, which he entered with a flask of wine given him by Maron. It was the cave of a

son of Poseidon and a nymphe named Thoosa, an enormous man-eating wild man named Polyphemos, who had one eye in

his forehead. When they had made a fire and sacrificed some kids, they sat down to dine; but the Kyklops

(Cyclops) came, and, after driving his flock inside, he barred the entrance with a great rock. When he saw the

men, he ate some.

Odysseus gave him some of Maron's wine to drink. He drank and demanded more, and after drinking that, asked

Odysseus his name. When Odysseus said that he was called Nobody, the Kyklops promised that he would eat Nobody

last, after the others: this was his act of friendship in return for the wine. The wine them put him to sleep.

Odysseus found a club lying in the cave, which with the help of four comrades he sharpened to a point; he then

heated it in the fire and blinded the Kyklops. Polyphemos cried out for help to the neighbouring Kyklopes, who

came and asked who was injuring him. When he replied ‘Nobody!’ they assumed he meant no one was

hurting him, so they went away again. As the flock went out as usual to forage for food, he opened the cave and

stood at the entrance with his arms spread out, and he groped at the sheep with his hands. But Odysseys bound

three rams together . . . Hiding himself under the belly of the largest one, he rode out with the flock.

Then he untied his comrades from the sheep, drove the flock to the ship, and as they were sailing off he shouted

to the Kyklops that it was Odysseus who had escaped through his fingers. The Kyklops had received a prophecy

from a seer that he would be blinded by Odysseus, and when he now heard the name, he tore loose rocks which he

hurled into the sea, just missing the ship. And from that time forward Poseidon was angry at Odysseus."

Plato, Laws 680b (trans. Lamb) (Greek philosopher C4th B.C.) :

"Everybody, I believe, gives the name of ‘headship’ [clan leadership] to the [most primitive

form of] government . . . And, of course, Homer mentions its existence in connection with the household system

of the Kyklopes (Cyclopes), where he says--No halls of council and no laws are theirs, ‘But within hollow

caves on mountain heights aloft they dwell, each making his own law. For wife and child; of others reck they

naught.’ . . . And now he appears to be confirming your statement admirably, when in his legendary account

he ascribes the primitive habits of the Kyklopes to their savagery."

Strabo, Geography 13. 1. 25 (trans. Jones) (Greek geographer C1st B.C. to C1st A.D.)

:

"Plato . . . sets forth as an example of the first stage of civilization the life of the Kyklopes

(Cyclopes) [i.e. as described by Homer], who lived on uncultivated fruits and occupied the mountain tops, living

in caves : ‘but all these things,’ he says, ‘grow unsown and unploughed’ for them

‘And they have no assemblies for council, nor appointed laws, but they dwell on the tops of high mountains

in hollow caves, and each is lawgiver to his children and his wives.’"

Pausanias, Description of Greece 8. 28. 1 (trans. Jones) (Greek travelogue C2nd A.D.)

:

"In the Odyssey he [Homer] relates how the Laistrygones (Laestrygones) [were] . . . not in the likeness of

men but of Gigantes, and he makes also the king of the Phaiakes (Phaeacians) say that the Phaiakes are near to

the gods like the Kyklopes (Cyclopes) and the race of Gigantes (Giants)."

Philostratus the Elder, Imagines 2. 18 (trans. Fairbanks) (Greek rhetorician C3rd

A.D.) :

"[Ostensibly a description of an ancient Greek painting at Neapolis (Naples) :] Kyklops (Cyclops). These

men harvesting the fields and gathering the grapes, my boy, neither ploughed the land nor planted the vines; but

of its own accord the earth sends forth these its fruits for them; they are in truth Kyklopes (Cyclopes), for

whom, I know not why, the poets will that the earth shall produce its fruits spontaneously. And the earth has

also made a shepherd-folk of them by feeding the blocks, whose milk they regard as both drink and meat. They

know neither assembly nor council nor yet houses, but they inhabit the clefts of the mountain.

Not to mention the others, Polyphemos son of Poseidon, the fiercest of them, lives here; he has a single eyebrow

extending above his single eye and a broad nose astride his upper lip, and he feeds upon men after the manner of

savage lions."

Ovid, Metamorphoses 14. 2 (trans. Melville) (Roman epic C1st B.C. to C1st A.D.)

:

"The Cyclopes' fields [of Sicily] that never knew the use of plough or harrow, nor owed any debt to teams

of oxen."

Ovid, Metamorphoses 15. 90 :

"With all the bounteous riches that the earth, Earth best of mothers, yields, can nothing please but savage

relish munching piteous wounds, a Cyclops' banquet?"

Pliny the Elder, Natural History 3. 89 (trans. Rackham) (Roman encyclopedia C1st

A.D.) :

"[Near Catania in Sicily :] Then come the three Rocks of the Cyclopes, the Harbour of Ulysses

[Odysseus]."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History 7. 9 :

"Some Scythian tribes, and in fact a good many, feed on human bodies--a statement that perhaps may seem

incredible if we do not reflect that races of this portentous character have existed in the central region of

the world [i.e. in Italy], named Cyclopes and Laestrygones."

Valerius Flaccus, Argonautica 4. 104 (trans. Mozley) (Roman epic C1st A.D.)

:

"The wild Cyclopes in Aetna's (Etna's) caverns watch the straits during stormy nights, should any vessel

driven by fierce south winds draw nigh, bringing thee, Polyphemus, grim fodder and wretched victims for thy

feasting, so look they forth and speed every way to drag captive bodies to their king. Them doth the cruel

monarch himself on the rocky verge of a sacrificial ridge, that looms above mid-sea, take and hurl down in

offering to his father Neptunus [Poseidon]; but should the men be of finer build, then he bids them take arms

and meet him with the gauntlets; that for the hapless men is the fairest doom of death."

Suidas s.v. Kyklopes (trans. Suda On Line) (Byzantine Greek Lexicon C10th A.D.)

:

"Kyklopes (Cycopes) : Wild men . . . It [Kyklopeion, Cyclopean] also signifies a mountain."

SOURCES

GREEK

- Homer, The Odyssey - Greek Epic C8th B.C.

- Plato, Laws - Greek Philosophy C4th B.C.

- Apollodorus, The Library - Greek Mythography C2nd A.D.

- Strabo, Geography - Greek Geography C1st B.C. - C1st A.D.

- Pausanias, Description of Greece - Greek Travelogue C2nd A.D.

- Philostratus the Elder, Imagines - Greek Rhetoric C3rd A.D.

ROMAN

- Ovid, Metamorphoses - Latin Epic C1st B.C. - C1st A.D.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History - Latin Encyclopedia C1st A.D.

- Valerius Flaccus, The Argonautica - Latin Epic C1st A.D.

BYZANTINE

- Suidas, The Suda - Byzantine Greek Lexicon C10th A.D.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

A complete bibliography of the translations quoted on this page.