KIRKE

Greek Name

Κιρκη

Transliteration

Kirkê

Latin Spelling

Circe

Translation

Hoop Round (kirkoô)

KIRKE (Circe) was a goddess of sorcery (pharmakeia) who was skilled in the magic of transmutation, illusion, and necromancy. She lived on the mythical island of Aiaia (Aeaea) with her nymph companions.

When Odysseus came to her island she transformed his men into beasts but, with the help of the god Hermes, he overcame her and forced her to end the spell.

Kirke's name is derived from the Greek verb kirkoô meaning "to secure with rings" or "hoop around"--a reference to the binding power of magic.

Kirke's island of Aiaia (Aeaea) was located in the far west, near the earth-encircling River Okeanos (Oceanus). Her brother Aeetes' realm in the far east was similarly named Aia (Aea).

FAMILY OF CIRCE

PARENTS

[1.1] HELIOS & PERSEIS (Homer Odyssey 10.135, Hesiod Theogony 956, Apollodorus 1.80, Apollonius Rhodius

4.584)

[1.2] HELIOS (Homer's Epigrams XIV, Hyginus Fabulae 199,

Ovid Metamorphoses 13.898, Valerius Flaccus 7.210)

[1.3] AEETES & HEKATE (Diodorus Siculus

4.45.1)

OFFSPRING

[1.1] AGRIOS, LATINOS (by Odysseus) (Hesiod Theogony 1011)

[1.2] TELEGONOS (by Odysseus) (Homerica Returns Frag 4, Homerica Telegony Frag 1,

Plutarch Greek Roman Parallel Stories 41, Hyginus Fabulae 127, Oppian Halieutica 2.497)

[1.3] NAUSITHOUS, TELEGONOS (by Odysseus) (Hyginus Fabulae 125)

[2.1] LATINOS (by Telemakhos) (Hyginus Fabulae 127)

[3.1] PHAUNOS (by Poseidon)

(Nonnus Dionysiaca 13.327 & 37.10)

ENCYCLOPEDIA

CIRCE (Kirkê), a mythical sorceress, whom Homer calls a fair-locked goddess, a daughter of Helios by the Oceanid Perse, and a sister of Aeëtes. (Od. x. 135.) She lived in the island of Aeaea; and when Odysseus on his wanderings came to her island, Circe, after having changed several of his companions into pigs, became so much attached to the unfortunate hero, that he was induced to remain a whole year with her. At length, when he wished to leave her, she prevailed upon him to descend into the lower world to consult the seer Teiresias. After his return from thence, she explained to him the dangers which he would yet have to encounter, and then dismissed him. (Od. lib. x.--xii.; comp. Hygin. Fab. 125.) Her descent is differently described by the poets, for some call her a daughter of Hyperion and Aerope (Orph. Argon. 1215), and others a daughter of Aeëtes and Hecate. (Schol. ad Apollon. Rhod. iii. 200.) According to Hesiod (Theog. 1011) she became by Odysseus the mother of Agrius. The Latin poets too make great use of the story of Circe, the sorceress, who metamorphosed Scylla and Picus, king of the Ausonians. (Ov. Met. xiv. 9, &c.)

AEAEA (Aiaia). A surname of Circe, the sister of Aeëtes. (Hom. Od. ix. 32; Apollon. Rhod. iv. 559; Virg. Aen. iii. 386.) Her son Telegonus is likewise mentioned with this surname. (Acaeus, Propert. ii. 23. § 42.)

Source: Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.

CLASSICAL LITERATURE QUOTES

PARENTAGE OF CIRCE

Homer, Odyssey 10. 135 ff (trans. Shewring) (Greek epic C8th B.C.) :

"Kirke (Circe), a goddess with braided hair, with human speech and with strange powers; baleful Aeetes was

her brother, and both were radiant Helios the sun-god's children; their mother was Perse, Okeanos' (Oceanus')

daughter."

Hesiod, Theogony 956 ff (trans. Evelyn-White) (Greek epic C8th or C7th B.C.)

:

"And Perseis, the daughter of Okeanos (Oceanus), bare to unwearying Helios (the Sun) Kirke (Circe) and

Aeetes the king."

Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 1. 80 (trans. Aldrich) (Greek mythographer C2nd A.D.)

:

"The Kholkhians (Colchians) who were ruled by Aeetes, the son of Helios and Perseis, and brother of Kirke

(Circe) and Minos' wife Pasiphae."

Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica 4. 584 ff (trans. Rieu) (Greek epic C3rd B.C.)

:

"Kirke (Circe), daughter of Perse and Helios."

Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 4. 45. 1 (trans. Oldfather) (Greek historian

C1st B.C.) :

"[A late rationalisation of the myth of Kirke (Circe) :] She [Hekate (Hecate), daughter of Perses the

brother of Aeetes] married Aeetes and bore two daughters, Kirke (Circe) and Medea, and a son Aigialeus."

CIRCE SETTLES ON THE ISLE OF AEAEA

Hesiod, Catalogues of Women Fragment 46 (from Scholiast on Apollonius Rhodius 3. 311)

(trans. Evelyn-White) (Greek epic C8th or C7th B.C.) :

"Apollonios (Apollonius), following Hesiod, says that Kirke (Circe) came to the island over against

Tyrrhenia on the chariot of Helios. And he called it Hesperian, because it lies towards the west."

Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica 3. 311 ff (trans. Rieu) (Greek epic C3rd B.C.)

:

"[Aeetes addresses the Argonauts :] ‘I myself was whirled along it in the chariot of my father Helios

(the Sun), when he took my sister Kirke (Circe) to the Western Land and we reached the coast of Tyrrhenia, where

she lives, far, far indeed from Kolkhis (Colchis).’"

Valerius Flaccus, Argonautica 7. 120 ff (trans. Mozley) (Roman epic C1st A.D.)

:

"Circe was borne away [from the land of Kolkhis (Colchis)] by winged Dracones (Dragons)."

CIRCE, THE ARGONAUTS & THE WEDDING OF MEDEA

Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica 4. 584 ff (trans. Rieu) (Greek epic C3rd B.C.)

:

"It [the talking beam of the ship Argo] threatened them [the Argonauts] with endless wanderings across

tempestuous seas till Kirke (Circe) should have purged them of the cruel murder of Apsyrtos (Apsyrtus) [Medea's

brother]; and it bade Polydeukes (Polydeuces) and Kastor ((Castor) beg the immortal gods to grant them access to

the Italian Sea, where they would find Kirke, daughter of Perse and Helios."

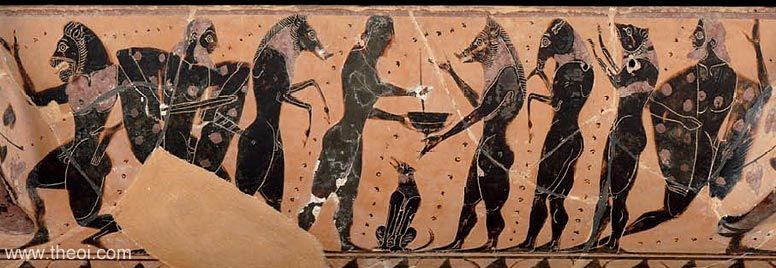

Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica 4. 662 ff :

"Passing swiftly over the Ausonian Sea, with the Tyrrhenian coast [of Italy] in sight, they [the Argonauts]

came to the famous haven of Aia (Aea), took Argo close in, and tied up to the shore.

Here they found Kirke (Circe) bathing her head in the salt water. She had been terrified by a nightmare in which

she saw all the rooms and walls of her house streaming with blood, and fire devouring all the magic drugs with

which she used to bewitch her visitors. But she managed to put out the red flames with the blood of a murdered

man, gathering it up in her hands; and so the horror passed. When morning came she rose from bed, and now she

was washing her hair and clothes in the sea.

A number of creatures whose ill-assorted limbs declared them to be neither man nor beast had gathered round her

like a great flock of sheep following their shepherd from the fold . . . The Argonauts were dumbfounded by the

scene. But a glance at Kirke's form and eyes convinced them all that she was the sister of Aeetes.

As soon as she had dismissed the fears engendered by her dream, Kirke set out for home, but as she left she

invited the young men to come with her, beckoning them on in her own seductive way. Iason Told them to take no

notice, and they all stayed where they were. But he himself, bringing Medea with him, followed in Kirke's steps

till they reached her house. Kirke, at a loss to know why they had come, invited them to sit in polished chairs;

but without a word they made for the hearth and sat down there after the manner of suppliants in distress. Medea

hid her face in her hands, Iason fixed in the ground his great hilted sword with which he had killed Apsyrtos

(Apsyrtus), and neither of them looked her in the face. So she knew at once that these were fugitives with

murder on their hands and took the course laid down by Zeus, the god of suppliants, who heartily abhors the

killing of a man, and yet as heartily befriends the killer. She set about the rites by which a ruthless slayer

is absolved when he seeks asylum at the hearth. First, to atone for the unexpiated murder, she took a suckling

pig from a sow with dugs still swollen after littering. Holding it over them she cut its throat and let the

blood fall on their hands. Next she propitiated Zeus with other libations, calling on him as the Cleanser, who

listens to a murderer's prayers with friendly ears. Then the attendant Naiades (Naiads) who did her housework

carried all the refuse out of doors. But she herself stayed by the hearth, burning cakes and other wineless

offerings with prayers to Zeus, in the hope that she might cause the loathsome Erinyes to relent, and that he

himself might once more smile upon this pair, whether the hands they lifted up to him were stained with a

kinsman's or a strangers blood.

When all was done she raised them up, seated them in polished chairs and taking a seat near by, where she could

watch their faces, she began by asking them to tell her what had brought them overseas, from what port they had

sailed to visit her and why they had sought asylum at her hearth. Horrible memories of her dream came back to

her as she wondered what was coming; and she waited eagerly to hear a kinwoman's voice, as soon as the girl had

looked up from the ground and she noticed her eyes. For all the Children of Helios were easy to recognise, even

from a distance, by their flashing eyes, which shot out rays of golden light.

Medea, daughter of Aeetes the black-hearted king, answered all her aunt's questions, speaking quietly in the

Kokhian (Colchian) tongue. She told her of the quest and voyage of the Argonauts, of their stern ordeal, and how

she herself had been induced to sin by her unhappy sister and had fled from her father's tyranny with Phrixos'

(Phrixus') sons; but she said nothing of the murder of Apsyrtos. Not that Kirke was deceived. Nevertheless she

felt some pity for her weeping niece.

‘Poor girl,’ she said, ‘you have indeed contrived for yourself a shameful and unhappy

home0coming; for I am sure you will not long be able to escape your father's wrath. The wrongs you have done are

intolerable, and he will soon be in Hellas to avenge his son's murder. However, since you are my suppliant and

kinswoman, I will not add to your afflictions now that you are here. But I do demand that you should leave my

house, you that have linked yourself to this foreigner, whoever he may be, this man of mystery whom you have

chosen without your father's consent. And do not kneel to me at my hearth, for I never will approve your conduct

and your disgraceful flight.’

Medea's grief, when she heard this, was more than she could bear. She drew her robe across her eyes and wailed

till Iason took her by the hand and led her out of doors shivering with fear. Thus they left Kirke's

house."

Strabo, Geography 5. 2. 6 (trans. Jones) (Greek geographer C1st B.C. to C1st A.D.)

:

"There is at Aithalia [in Italy] a Port Argoos, from the ship ‘Argo’, as they say; for when

Iason (Jason), the story goes, was in quest of the abode of Kirke (Circe), because Medea wished to see the

goddess, he sailed to this port."

Valerius Flaccus, Argonautica 7. 210 ff (trans. Mozley) (Roman epic C1st A.D.)

:

"Of a sudden Venus [Aphrodite] was sitting on her [Medea's] bed, changed as she was from heavenly shape and

counterfeiting Circe, Titan's [Helios'] daughter, with broidered robe and magic wand. But the girl, as though

mocked by the lingering image of a dream, gazes perplexed and only little by little deems her to be the sister

of her mighty sire; then in tearful joy she sprang forward and of her own accord kissed the cruel goddess, and

first addressed her : ‘Circe! At last, scarce at last, cruel one! Restored to thine own--why did the yoked

snakes bear thee hence in flight? What sojourning was more pleasing to thee than my father's land . .

.’

Then Venus [masquerading as Circe] checks further speech and thus rejoins : ‘Thou alone art the cause of

this my journey; I come knowing long since thou art no longer a child; spare thy complaints, nor blame me who

have chosen a better lot; nay, that now we may bear in mind heaven's gifts, deem rather that this world is

shared by all living souls, and shared too are the gods. Call that thy country where the sun goes forth and back

again; seek not, my child, with unfeeling heart to imprison me in this eternal cold. I had a right--as thou too

hast--to leave the unprofitable Colchians. And now am I Ausonian Picus' royal consort, nor are my meadows there

unsightly with flame-breathing bulls: in me thou beholdest the mistress of the Tuscan Sea. But what kind of

suitors are the Sauromatae for thee, poor child? . . .’

Straightway she spoke in answer, scorning the goddess' words : ‘Not so forgetful of great Perseis [Hekate]

doest thou see me as to be driven, a hapless victim, into such wedlock.’ [I.e., she has her magic to fall

back to avoid such a marriage.]"

CIRCE & ODYSSEUS

Homer, Odyssey 10. 135 - 12. 156 (trans. Shewring) (Greek epic C8th B.C.)

:

"[Odysseus sailed forth from the land of the Laistrygones (Laestrygones) and came next to the island of

Kirke (Circe) :] Then we came to the island of Aiaia (Aeaea); here Kirke (Circe) dwelt, a goddess with braided

hair, with human speech and with strange powers; the magician Aeetes was her brother, and both were radiant

Helios the sun-god's children; their mother was Perse, Okeanos' (Oceanus') daughter. We brought the ship

noiselessly to shore, and with some divinity for guide we put in at the sheltering harbour. We disembarked, and

for two days and two nights we lay there, eating out our hearts with sorrow and weariness.

But when Eos the Dawn of the braided hair brought the third day at last, I took my spear and my sharp sword and

hastened up to a vantage-point, hoping to see some human handiwork or to catch the sound of some human speech. I

climbed a commanding crag, and from where I stood had a glimpse of smoke rising from the ground. There were

gleams of fire through the smoke, and at sight of this I wondered inwardly whether to go and look. But as I

pondered, it seemed a wiser thing to return first to my vessel on the beach, give my men a meal and then send

them out to spy. I was on my way back and near the ship when some divinity pities me in my loneliness and sent a

great antlered stag right across my path [perhaps a man that Kirke had transformed into an animal]; it was going

down to its feeding-ground in the wood to drink the river-water . . . As it left the wood I struck it upon the

spine, half-way down the back. The spear of bronze went right through, and with one cry the stag fell in the

dust and its breath departed . . .

Eos the dawn comes early, with rosy fingers. When she appeared, I assembled all my men together and thus

addressed them : ‘Comrades, as things now are, we do not know where the region of dawn or of darkness

lies, in what quarter the radiant sun sinks below the earth or in what quarter he rises up. Let us ask ourselves

quickly if some good plan may yet be found, though I fear there is none. When I climbed that commanding crag, I

could see that we were in an island encircled by boundless ocean. The main part of the land lies low, and in the

mid-point of it I saw smoke rising across thick undergrowth and woodland.’

So I spoke and their hearts quailed within them as they thought again of the deeds of Antiphates the Laistrygon

(Laestrygonian) and the fierce and fearful and man-devouring Kyklopes (Cyclopes). They wept aloud, and the great

tears rolled down their cheeks, though lamentation availed them nothing.

I divided my crew into two companies, and gave each its own leader; I myself captained one, Eurylokhos

(Eurylochus) the other. Then we shook the lots in a bronze helmet, and the lot that leapt out was that of bold

Eurylokhos. So he went on his way, and twenty-two comrades with him; themselves in tears, they left the rest of

us weeping too. In the glades they found the palace of Kirke (Circe), built of smooth stones on open ground.

Outside, there were lions and mountain wolves that she had herself bewitched by giving them magic drugs. The

beasts did not set upon my men; they reared up, instead, and fawned on them with their long tails. As dogs will

fawn around their master when he comes home from some banquet, because he never fails to bring back for them a

morsel or two to appease their craving, so did these lions, these wolves with their powerful claws, circle

fawningly round my comrades. The sight of the strange huge creatures dismayed my men, but they went on and

paused at the outer doors of the goddess of braided hair. And now they could hear Kirke within, singing with her

beautiful voice as she moved to and fro at the wide web that was more than earthly--delicate, gleaming,

delectable, as a goddess' handiwork needs must be--a goddess or a woman, moving to and fro at her wide web and

singing a lovely song that the whole floor re-echoes with.. Then Polites spoke to the rest there ‘Come,

let us make ourselves heard at once.’

So he spoke. The men called out and made themselves heard; she came forth at once, she opened the shining doors,

she called them to her, and in their heedlessness they all entered, all but Eurylokhos; he stayed outside,

foreboding mischief. The goddess ushered them in, gave them all seats, high or low, and blended for them a dish

of cheese and of barley-meal, of yellow honey and Pramnian wine, all together; but with these good things she

mingled pernicious drugs as well, to make them forget their own country utterly. Having given them this and

waited for them to have their fill, she struck them suddenly with her wand, then drove them into the sties where

she kept her swine. And now the men had the form of swine--the snout and grunt and bristles; only their minds

were left unchanged. They shed tears as they were shut in, while Kirke threw down in front of them some acorns

and mast and cornel--daily fare for swine whose lodging is on the ground.

Eurylokhos hastened back to the ship to tell the news of his comrades' dismal fate. But for all his zeal he

could not bring out one word, so wrung was hi heart with its great sorrow; the tears were standing in his eyes,

and his thoughts were all of lamentation. We questioned him, all of us, in bewilderment, and at last he found

plain words to tell how our other friends had been lost to us : ‘Noble Odysseus, we went, as you bade us,

through the thickets, and in the glades we found before us a stately palace. Someone inside it, a goddess or a

woman, was singing in high pure notes as she moved to and fro at her wide web. The men called out and made

themselves heard; she came out at once, she opened the shining doors and she called them to her. They in their

heedlessness all entered; only I myself foreboded mischief and stayed outside. They vanished utterly, all of

them; not one among them appeared again, though I sat a long while there, keeping watch.’

So he spoke. I slung across my shoulders my great silver-studded sword of bronze; I slung on my bow as well,

then told him to guide me back by the same path. But he clutched my knees with both his hand and made

supplication : ‘Heaven-favoured king, do not force me back that way again; leave me here. I know you will

neither return yourself nor yet bring back any of your comrades. Instead, let us flee from this place at once,

taking these others with us; we may still escape the day of evil.’

Such were his words. I answered thus : ‘So be it, Eurylokhos; keep your own place here, eating and

drinking beside the ship; I must go yonder; stern necessity is upon me.’

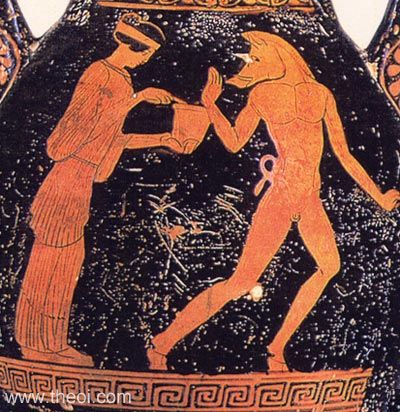

And with that I left the ship and shore and took the path upward; but as I traversed those haunted glades, as I

came close to Kirke's house and neared the palace of the enchantress, I was met by golden-wanded Hermes; he

seemed a youth in the lovely spring of life, with the first down upon his lip. He seized my hand and spoke thus

to me : ‘Luckless man, why are you walking thus alone over these hills, in country you do not know? Your

comrades are yonder in Kirke's grounds; they are turned to swine, lodged and safely penned in the sites. Is your

errand her to rescue them? I warn you, you will never return yourself, you will only be left with the others

there. Yet no--I am ready to save you from all hazards, ready to keep you unscathed. Look. Here is a herb of

magic virtue; take it and enter Kirke's house with it; then the day of evil never will touch your head. I will

tell you of all her witch's arts. She will brew a potion for you, but with good things she will mingle drugs as

well. Yet even so, she will not be able to enchant you; my gift of the magic herb will thwart her. I will tell

you the rest, point by point. When Kirke strikes you with the long wand she has, draw the keen sword from beside

your thigh, rush upon her and make as if to kill her. She will shrink, back, and then ask you to lie with her.

At this you must let her have her way; she is a goddess; accept her bed, so that she may release your comrades

and make you her cherished guest. But first, make her swear the great oath of the Blessed Ones [by the river

Styx] to plot no mischief to you thenceforward--if not, while you lie naked there, she may rob you of courage

and of manhood.’

So spoke the Radiant One; then gave the magic herb, pulling it from the ground and showing me in what form it

grew; its root was black, its flower milk-white. Its name among the gods is moly. For mortal men it is perilous

to pluck it up, but for the gods all things are possible.

Then Hermes departed over the wooded island went his way to the mountain of Olympos. I myself passed on to

Kirke's palace, with my thoughts in turmoil as I walked. I paused at the doorway of the goddess, and standing

there I gave a great cry; she heard my voice and came out quickly, opening the shining doors and calling me in.

I went up to her though my heart sank. She ushered me in and gave me a tall silver-studded chair to sit

in--handsome and cunningly made it was--with a stool beneath it for the feet. In a golden goblet she brewed a

potion for me to drink, and treacherously mingled her drug with it. When I had taken and drunk it up and was

unenchanted still, she struck at me with her wand, and ‘Now’ she said ‘be off to the sty, to

wallow with your companions there.’

So she spoke, but I drew the keen sword from beside my thigh, rushed at her and made as if to kill her. She

shrieked, she slipped underneath my weapon, she clasped my knees and spoke in rapid appealing words: ‘Who

are you, and from where? Where are your city and your parents? It bewilders me that you drank this drug and were

not bewitched. Never has any other man resisted this drug, once ha head drunk it and let it pass his lips. But

you have an inner will that is proof against sorcery. You must surely be that man of wide-ranging spirit,

Odysseus himself; the Radiant One of the golden wand [Hermes] has told me of you; he always said that Odysseus

would come to me on his way from Troy in his dark and rapid vessel. But enough of this; sheathe your sword; then

let us go to bed together, and embracing there, let us learn to trust in one another.’

So she spoke, but I answered her : ‘Kirke, how can you ask me to show you gentleness? In this very house

you have turned my comrades into swine, and now that you have me also here you ask me in your treacherousness to

enter your room and lie with you, only that when I lie naked you may rob me of courage and of manhood. Never,

goddess, could I bring myself to lie with you unless you consented first to swear a great oath to plot no

mischief to me henceforward.’

So I spoke, and she swore at once the thing I asked for. When Kirke had uttered the due appointed words, I lay

down at last in her sumptuous bed.

All this while, four handmaids of hers were busying themselves about the palace. She has them for her household

tasks, and they come from springs [Naiades], they come from groves [Dryades], they come from the sacred rivers

flowing seawards [Naiades]. One spread the chairs with fine crimson covers above and with linen cloths beneath;

in front of the chairs, a second drew up silver tables on which she laid gold baskets for bread; a third mixed

honey-sweet lovely wine in a silver bowl sand set the golden goblets out; the fourth brought water and lit a

great fire under a massive cauldron. The water warmed; and when it boiled in the bright bronze vessel, the

goddess made me sit in a bath and bathed me with water from the cauldron, tampering hot and cold to my mind and

pouring it over my head and shoulders until she had banished from my limbs the weariness that had sapped my

spirit. And having washed me and richly appointed me with oil, she dressed me in a fine cloak and tunic, led me

forward and gave me a tall silver-studded chair to sit on--handsome and cunningly made--with a stool beneath it

for the feet. She bade me eat, but my heart was not on eating, and I sat with my thoughts elsewhere and my mind

unquiet.

When Kirke saw me sitting thus, not reaching for food but sunk in despondency, she came and stood near me,

quickly questioning : ‘Odysseus, why do you sit there tongue-tied eating your heart out, not touching food

or drink? Can it be that you fear some further treachery? You should have no doubts; I have sworn the great oath

already.'

So she spoke, but I answered her : `Kirke, what man of righteous thoughts could bring himself to taste food or

drink before winning liberty for his friends and seeing the men before his eyes? If it is in earnest that you

tell me to eat and drink, release them now, and let me see my trusty companions face to face.’

So I spoke, and Kirke went through the hall and out, wand in hand; she flung open the doors of the sty and set

the men running out in the shape of fat and full-grown swine. Then they stood facing her, and she went to and

fro among them, anointing them one by one with another charm. Their limbs began to shed the bristles that

Kirke's poison had planted on them, and they became men again, but younger than they had been before, and taller

and handsomer to the eye. They knew me at once, and man after man they clasped my hand. A melting mood stole

upon them all, and they sobbed aloud till the house re-echoed dolefully. Kirke herself felt compassion; then she

came up and said to me : ‘Son of Laertes, subtle Odysseus, now go back to your rapid vessel by the beach.

First, with your men, haul the ship ashore; then fetch out all your gear and goods and stow them inside the

caves; then return yourself and bring your trusty companions with you.’

Such were her words, and my own heart desired nothing better. I went my way to the rapid vessel by the beach,

and there I found my comrades aboard; they were shedding big tears and lamenting piteously . . . Lamenting they

spoke to me in words that went home: ‘Heaven-favoured king, we are as happy at your return as if we had

reached our own native land again, Ithaka (Ithaca) itself. But now you must tell from first to last how our

other friends were lost to us.’

So they spoke; I answered them with consoling words : ‘First let us haul the ship ashore, then take out

all our gear and goods and stow them inside the caves; after that, make haste to come with me, all of you, and

to see your friends in the goddess Kirke's palace, eating and drinking; they have enough and to

spare.’

So I spoke, and the men were quick to do my bidding; only Eurylokhos endeavoured to keep them back :

‘Wretched men, where are we going? Why do you court disaster thus, why venture down to Kirke's dwelling?

She will turn us all into swine or wolves or lions, to guard her palace whether we will or no; just as the

Kyklopes (Cyclopes) penned our companions in when they reached his steading--foolhardy Odysseus went in with

them, and his presumption was their undoing.’

So he spoke; I was half minded to draw the long keen sword from my sturdy thigh, strike off his head and send it

to meet the ground, although he was close of kin to me; but my men all round me restrained me with pacifying

words : ‘Heaven-born one, let us leave this man, if you consent, to stay by the ship and guard it. As for

the rest of us, we ask you to guide us on the way to the palace of the goddess Kirke.’

And with these words they began to walk, leaving the vessel and the sea. Nor did Eurylokhos linger there; he

came with the rest, dreading my powerful indignation.

In the meantime inside her palace Kirke had bathed the others hospitably, had richly anointed them with oil and

had clothed them in tunics and fleecy cloaks; we found them dining in the hall, every man of them. When the two

groups spied each other--when the men looked each other in the face--they began to weep and make lamentation

till the house around them echoed with it. But the goddess came up and said to me : ‘Son of Laertes,

subtle Odysseus, you must all give over these loud lamentations you are making. I myself well know what

tribulations you have endured on the teeming sea and what injustices you have borne from barbarous men on land.

But enough! Eat your food and drink your wine till you have regained the same spirit that you had when you first

set sail from your own country, rocky Ithaka. You are listless now, you are spiritless, brooding for ever and

for ever on the calamities of your wanderings. Your hearts are never disposed to mirth, because you have

suffered all too much.’

Such were her words, and our hearts accepted them.

"So every day, till the year's end, we sat there feasting on plenteous meat and delicious wine. When the

year was out and the seasons had circled round, then my comrades called me apart and said : ‘Forgetful

man, it is time now to call your own land to mind once more, if indeed heaven means you tom come safe home to

your lofty house and the country of your fathers.’

Such were their words, and my heart accepted them. So all that day, till the sun set, we sat and feasted on

plenteous meat and delicious wine. When the sun went and darkness came, the men lay down to sleep in the shadowy

halls, but I, returning to Kirke's sumptuous bed, clasped her knees and made supplication to her, and the

goddess heard my plea : ‘Kirke, you gave me once your promise to help me homewards, and the time has come

to make it good; my own desire is set that way, and the desire of my comrades also--they are there around me,

vexing my heart with their lamentations when once you yourself are out of sight.’

The goddess answered my words forthwith : ‘Son of Laertes, subtle Odysseus, if it is in spite of

yourselves that you all stay in my palace still, then you must stay here no longer. But another path must be

travelled first; you must visit the house of dread Persephone and of Haides, and there seek counsel from the

spirit of Theban Teiresias (Tiresias). The blind seer's thought is wakeful still, for to him alone, even after

death, Persephone has accorded wisdom; the other dead are but flitting shadows.’

So she spoke; my spirit was crushed within me. I sank down on the bed and wept, and my heart lost the desire to

live or to look longer upon the sunlight. I wept, I writhed till the bout of bitterness was past. At length I

answered and said to her : ‘But Kirke, who will pilot me on my voyage? Never since time began has the dark

ship of any traveller brought him to Haides' house.’

And at once the goddess answered me : ‘Son of Laertes, subtle Odysseus, when you reach your ship, no lack

of a pilot need trouble you. Raise the mast, spread the white sail and seat yourself : the north wind's

breathing will waft the vessel on. When you have sailed through the river Okeanos (Oceanus), you will see before

you a narrow strand and the groves of Persephone's--the tall black poplars, the willows with their self-wasted

fruit; then beach the vessel beside deep-eddying Okeanos and pass on foot to the dank domains of Haides. At the

entrance there, the stream of Akheron (Acheron) is joined by the waters of Pyriphlegethon and of a branch of

Styx, Kokytos (Cocytus), and there is a rock where the two loud-roaring rivers meet. Then, Lord Odysseus, you

must do as I enjoin you; [N.B. She then instructs Odysseus in the art of necromancy:] go forward, and dig a

trench a cubit long and a cubit broad; go round this trench, pouring libation for all the dead, first with milk

and honey, then with sweet wine, then with water; and sprinkle white barley-meal above. Then with earnest

prayers to the strengthless presences of the dead you must promise that when you have come to Ithaka you will

sacrifice in your palace a calfless heifer, the best you have, and will load a pyre with precious things; and

that for Teiresias and no other you will slay, apart, a ram that is black all over, the choicest of the flocks

of Ithaka.

‘When with these prayers you have made appeal to the noble nations of the dead, then you must sacrifice a

ram and a black ewe; bend the victim's heads down towards Erebos (Erebus), but turn your own head away and look

towards the waters of the river. At this, the souls of the dead and gone will come flocking there. With

commanding voice you must call your comrades to flay and burn the two sheep that now lie before them, killed by

your own ruthless blade, and over them to pray to the gods, to resistless Haides and dread Persephone. As for

yourself, draw the keen sword from beside your thigh; then, sitting down, hold back the strengthless presences

of the dead from drawing nearer to the blood until you have questioned Teiresias. Then, King Odysseus, the seer

will come to you very quickly, to prophesy the path before you, the long stages of your travel, and how you will

reach home at last over the teeming sea.'

Scarcely had she ended her words when Eos the Dawn appeared in her flower cloth of gold. Kirke gave me my tunic

and cloak to wear; she herself put on a big silvery mantle, graceful and delicate; she fastened a lovely gold

girdle round her waist and slipped a scarf over her head. Then I went through the halls and roused my comrades,

standing near each in turn and uttering persuasive words : ‘You have slept enough; give over that drowsy

pleasure now. It is time to go--Lady Kirke has shown me how and where.’

So I spoke; and the men agreed gladly enough. Yet not even from this adventure could I bring my comrades away

unscathed. There was one of them called Elpenor, the youngest of all, neither brave in battle nor firm in mind;

he had left the rest of my company and had lain down on the top of Kirke's house, heavy with wine and seeking

the cool. When my comrades began to stir and he heard the sound of their feet and voices, he leapt up in haste

and quite forgot to take the long ladder downwards and so return. Instead, he fell headlong from the roof; his

neck was wrenched away from the spine, and his would went down to the house of Haides.

As the rest came out I had words to say to them : ‘Doubtless you think you are on your way to your own

homes, to your own country. But no; Kirke has said we must sail elsewhere, to the house of Haides and dread

Persephone; we are to ask counsel there of Theban Teiresias.’

So I spoke, and their hearts were crushed within them. They sank down on the ground where they were and began to

groan and tear their hair; but no good could come of this lamentation.

While we made our melancholy way to the ship at the sea's edge, weeping without restraint, Kirke already had

passed before us and tethered a ram and a black ewe beside the vessel. She had slipped past us unperceived; what

eyes could discern a god in his comings and his goings if the god himself should wish it otherwise?

We reached our ship at the sea's edge and hauled it down to the bright water, then stowed the mast and the sails

inside; we took the sheep and put them aboard; last of all, we ourselves embarked, still despondent, weeping

still unrestrainedly. But Kirke of the braided tresses, the goddess of awesome powers and of human speech, sent

the best of comrades after our dark-prowed vessel, a following breeze to fill our sails. We made fast the

tackling everywhere, then seated ourselves while wind and the helmsman bore the ship forward on her course. The

sails were taut as she sped all day across the sea till the sun sank and light thickened on every pathway.

The vessel came to the bounds of eddying Okeanos (Oceanus), where lie the land and the city of the Kimmerians

(Cimmerians), covered with mist and cloud. [N.B. The Kimmerians were a Skythian (Scythian) tribe who lived north

of the Kaukasos (Caucasus), Homer places the island of Kirke in this eastern region.] Never does the resplendant

sun look on this people with his beams, neither when he climbs towards the stars of heaven nor when once more he

comes earhtwards form the sky; dismal gloom overhands these wretches always . . . [Odysseus reaches the borders

of Haides and performs the rites of necromancy as instructed by Kirke before returning to her island.]

The ship in due course left the waters of the river Okeanos and reached the waves of the spacious sea and the

island of Aiaia (Aeaea; it is there that Eos the Dawn the early comer has her dwelling place and her

dancing-ground, and Helios the sun himself has his risings. [N.B. gain Homer clearly places Aiaia in the

farthest East.] We came in; we beached our vessel upon the sands and disembarked upon the sea-shore; there we

fell fast asleep, awaiting ethereal Eos the Dawn.

Eos the Dawn comes early, with rosy fingers. When she appeared I sent my comrades to Kirke's palace to fetch the

body of dead Elpenor [and buried the man as Odysseus had promised his ghost in Haides] . . .

Our coming back did not escape the watchfulness of Kirke. She attired herself and hastened towards us, while the

handmaidens with her brought bread and meat in plenty, and glowing red wine. Then, coming forward to stand among

us, the queenly goddess began to speak : ‘Undaunted men who went down alive to Haides' dwelling, men fated

to taste death twice over, while other men taste of it but once,--come now, eat food and drink wine here all

day. At break of morning you must set sail, and I myself will tell you the way and make each thing clear, so

that no ill scheming on sea or land may bring you to misery and mischief.’

Such were her words, and our own hearts accepted them. So all that day, till the sun set, we sat and feasted on

plenteous meat and delicious wine. When the sun went and darkness came, my men lay down to sleep by the vessel's

hawsers, but as for myself, the goddess took me by the hand and made me sit down apart; she lay down near me and

questioned me about everything, and I told her all from first to last. Then Lady Kirke began again : ‘The

things you speak of are all fulfilled, then; but listen now to my further words--later, without your seeking it,

some god will recall them to your mind. You will come to the Seirenes first of all; they bewitch any mortal who

approaches them. If a man in ignorance draws too close and catches their music, he will never return to find

wife and little children near him and to see their joy at his homecoming; the high clear tones of the Seirenes

(Sirens) will bewitch him. They sit in a meadow; men's corpses lie heaped up all around them, mouldering upon

the bones as the skin decays. You must row past there; you must stop the ears of all your crew with sweet wax

that you have kneaded, so that none of the rest may hear the song. But if you yourself are bent on hearing, then

give them orders to bind you both hand and foot as you stand upright against the mast-stay, with the rope-ends

tied to the mast itself; thus you may heart he two Seirenes' voices and be enraptured. If you implore your crew

and beg them to release you, then they must bind you fast with more bonds again.

‘When your crew have rowed past the Seirenes, I will not expressly say to you which of two ways you ought

to take; you must follow your own counsel there; I will only give you knowledge of them both. On the one side

are overshadowing rocks against which dash the mighty billows of the goddess of blue-glancing seas [Amphitrite].

The blessed gods call these rocks the Wanderes; even things that fly cannot pass them safely, not even the

trembling doves that carry ambrosia to Father Zeus; even of those the smooth rock always seizes one, and the

Father sends another in to restore the number. Nor has any ship carrying men ever come there and gone its way in

safety; the ship's timbers, the crew's dead bodies are carried away by the sea waves by blasts of deadly fire.

One alone among seagoing ships did indeed sail past on her way home from Aeetes' kingdom--this was Argo [who

also stopped at Kirke's island on their return voyage], whose name is on all men's tongues; and even she would

soon have been dashed against the great rocks had not Hera herself, in her love for Iason (Jason), sped the ship

past.

‘On the other side are a pair of cliffs. One of them with its jagged peak reaches up to the spreading sky,

wreathed in dark cloud that never parts. Theer is no clear sky above this peak even in summer or harvest-time,

nor could any mortal man climb up it or get a foothold on it, not if he had twenty hands and feet; so smooth is

the stone, as if it were all burnished over. Half-way up the cliff is a murky cave, facing north-west to Erebos,

and doubtless it is past this, Odysseus, that you and your men will steer your vessel. A strong man's arrow shot

from a ship below would not reach the recesses of that cave. Inside lives Skylla (Scylla), yelping hideously;

her voice is no deeper that a young puppy's, but she herself is a fearsome monster; no one could see her and

still be happy, not even a god if he went that way. She has twelve feet all dangling down, six long necks with a

grisly head on each of them, and in each head a triple row of crowded and close-set teeth, fraught with black

death. Sunk waist-deep in the cave's recesses, she still darts out her head from that frightening hollow, and

there, groping greedily round the rock, she fishes for dolphins and for sharks and whatever beast more huge than

these she can seize upon from all the thousands that have their pasture from the queen of the loud moaning seas

[Amphitrite]. No seaman ever, in any vessel, has boasted of sailing that way unharmed, for with every single

head of hers she snatches and carries off a man from the dark-prowed ship.

‘You will see that the other cliff lies lower, no more than an arrow's flight away. On this there grows a

great leafy fig-tree; under it, awesome Kharybdis (Charybdis) sucks the dark water down. Three times a day she

belches it forth, three times in hideous fashion she swallows it down again. Pray not to be caught there when

she swallows down; Poseidon himself could not save you from destruction then. No, keep closer to Skylla's cliff,

and row past that as quickly as may be; far better to lose six men and keep your ship than to lose your men one

and all.’

So she spoke, and I answered her : ‘Yes, goddess, but tell me truly--could I somehow escape this dire

Kharybdis and yet make a stand against the other when she sought to make my men her prey?’

So I spoke, and at once the queenly goddess answered : ‘Self-willed man, is your mind then set on further

perils, fresh feats of war? Will you not bow to the deathless gods themselves? Skylla is not of mortal kind; she

is a deathless monster, grim and baleful, savage, not be wrestled with. Against her there is no defence, and the

best path is the path of flight. If you pause to arm beside that rock, I fear that she may dart out again, seize

again with as many heads and snatch as many men as before. No, row hard and invoke Krataeis (Crataeis); she is

Skylla's mother; it is she who bore her to plague mankind; Krataeis will hold her from darting twice.

‘Then you will reach the isle of Thrinakia (Thrinacia). In this there are grazing many cows and many fat

flocks of sheep; they are Helios the Sun-God's [Helios']--seven herds of cows and as many fine flocks of sheep.

In each herd and each flock there are fifty beasts; no births increase them, no deaths diminish them. They are

pastured by goddesses, lovely-haired Nymphai (Nymphs) named Phaethousa (Phaethusa) and Lampetie (Lampetia),

whose father is the sun-god Hyperion and whose mother is bright Neaera; having borne and bred them, she took

them away to remote Thrinakia to live there and tend their father's sheep and the herds with curling horns. If

you leave these unharmed--if you set your mind only on return--you may all of you still reach Ithaka, though

with much misery. But if you harm them, then I foretell destruction alike for your ship and for your comrades,

and if you yourself escape that end, you will return late and in evil plight, having lost for ever all your

comrades.’

Scarcely had she ended her words when Eos the Dawn appeared in her flowery cloth of gold. Then queenly Kirke

took her way back across the island; I went to my ship and told my comrades to go aboard and loose the hawsers.

They embarked forthwith, sat at the thwarts and, grouped in order, dipped their oars in the whitening sea. And

Kirke of the braided tresses, the goddess of awesome powers and of human speech, sent the best of comrades after

our dark-powered vessel, a following breeze to fill our sails. We made fast the tackling everywhere, then seated

ourselves while wind and helmsman bore the ship forward on her course.

Then with heavy heart I spoke to my comrades thus : `Friends, it is not right that only one man, or only two,

should know the divine decrees that Lady Kirke has uttered to me. I will tell you of them, so that in full

knowledge we may die or in full knowledge escape, it may be, from death and doom."

Homer, Odyssey 8. 447 ff :

"[Odysseus] hastened to tie the cunning knot which Lady Kirke (Circe) had brought to his knowledge in other

days."

Homer, Odyssey 9. 23 ff :

"Subtle Aiaian Kirke (Aeaean Circe) confined me in her palace and would have had me for husband."

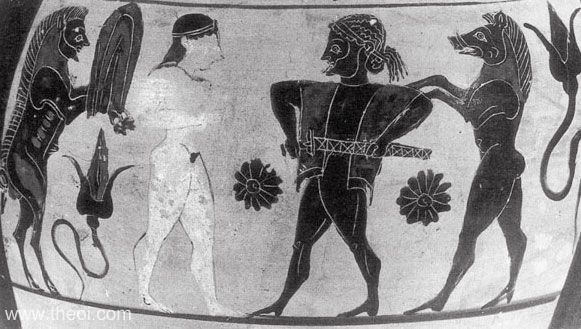

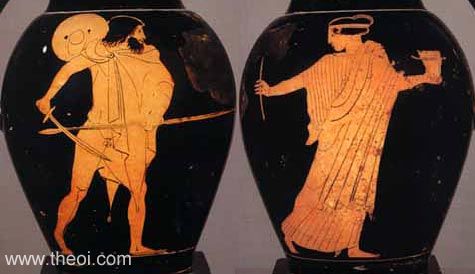

Aeschylus, Circe (lost play) (Greek tragedy C5th B.C.) :

Aeschylus' lost satyr-play Circe told the story of Odysseus' encounter with the witch Circe.

Vase paintings from the period suggest that Odysseus' half-transformed animal-men formed the chorus in place of

the usual Satyrs.

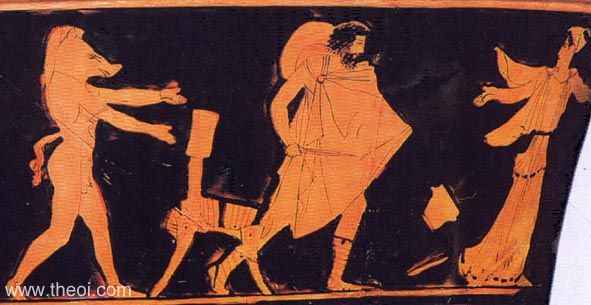

Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca E7. 14 - 19 (trans. Aldrich) (Greek mythographer C2nd

A.D.) :

"With his one ship he [Odysseus] reached Aiaia (Aeaea). Kirke (Circe) lived here, a daughter of Helios and

Perse, and the sister of Aeetes. She was skilled in the use of all charms, potions, and spells. Odysseus divided

his men by lot into two groups. He himself fell into the group that remained at the ship, and Eurylokhos

(Eurylochus) went off with twenty-two comrades to see Kirke. When she invited them in, they all entered except

Eurylokhos. She gave each one of them a potion of cheese, honey, barley-groats, and wine, into which she had

mixed a drug. When they had drunk it, with a touch of her wand she changed them into different shapes, some into

wolves, some pigs, some asses, and some into lions. Eurylokhos reported all this to Odysseus after he had

watched it happen. Odysseus went to see Kirke with some moly, which Hermes had given him, and by adding it to

her drugs he alone was able to drink without being enchanted. He then drew his sword with the thought of slaying

Kirke, but she mollified him and gave his comrades back their shapes. And after she swore not to hurt him,

Odysseus slept with her, and fathered Telegonos (Telegonus). After lingering there for a year, Odysseus sailed

the Ocean, offered sacrifices to the souls of the dead, and, following Kirke's instructions, asked for

prophecies from Teiresias (TIresias) . . . After returning to Kirke, Odysseus was sent on his way by her.

As Odysseus sailed past, he wanted to hear their [the Seirenes (Sirens)] song, so, following Kirke's

instructions, he plugged the ears of his comrades with wax, and had them tie him to the mast."

Lycophron, Alexandra 672 ff (trans. Mair) (Greek poet C3rd B.C.) :

"What beast-molding Drakaina (She-Dragon) [Kirke (Circe)] shall he [Odysseus] not behold, mixing drugs with

meal, and beast-shaping doom? And they, hapless ones, bewailing their fate shall feed in the pigstyes, crunching

grapestones mixed with grass and oilcake. But him the drowsy root shall save from harm and the coming of Ktaros

[Hermes]."

Pausanias, Description of Greece 5. 19. 7 (trans. Jones) (Greek travelogue C2nd A.D.)

:

"[Amongst the scenes depicted on the chest of Kypselos (Cypselus) dedicated at Olympia :] There is a grotto

and in it a woman sleeping with a man upon a couch. I was of opinion that they were Odysseus and Kirke (Circe),

basing my view upon the number of the handmaidens in front of the grotto and upon what they are doing. For the

women are four, and they are engaged on the tasks which Homer mentions in his poetry."

Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae 1. 10e (trans. Gullick) (Greek rhetorician C2nd to C3rd

A.D.) :

"[A late Greek rationalisation of the Kirke (Circe) myth :] By way of denouncing drunkenness the poet

[Homer] . . . changes the men who visited Kirke into lions and wolves because of their self-indulgence, whereas

Odysseus is saved because he obeys the admonition of Hermes, and therefore comes off unscathed."

Ptolemy Hephaestion, New History Book 4 (summary from Photius, Myriobiblon 190)

(trans. Pearse) (Greek mythographer C1st to C2nd A.D.) :

"The plant moly of which Homer speaks; this plant had, it is said, grown from the blood of the

Gigante (Giant) killed in the isle of Kirke (Circe); it has a white flower; the ally of Kirke who killed the

Gigante was [her father] Helios; the combat was hard (Greek malos) from which the name of this

plant."

Anonymous, Odyssey Fragment (trans. Page, Vol. Select Papyri III, No. 137) (Greek

epic C3rd-4th A.D.) :

"Unhappy Elpenor, whom Kirke's (Circe's) palace stole away."

Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 125 (trans. Grant) (Roman mythographer C2nd A.D.)

:

"He [Odysseus] came to the island of Aenaria, to Circe, daughter of Sol [Helios], who, by giving a potion,

used to change men into wild beasts. When he sent Eurylochus to her with twenty-two of his men, she changed them

from human form; but Eurylochus in fear did not enter, but fled and reported to Ulysses. Ulysses himself alone

went to her, but on the way Mercurius [Hermes] gave him a charm, and showed him how to deceive Circe. After he

came to Circe and took the cup from her, at Mercurius' [Hermes] suggestion he put in the charm, and drew his

sword, threatening to kill her unless she restored his comrades. Then Circe knew that this had not happened

without the will of the gods, and so, promising that she would not do the like to him, she restored his comrades

to their earlier forms. She herself lay with him, conceived, and bore two sons, Nausithous and Telegonus."

Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 125 :

"He [Odysseus] came to the Sirenes (Sirens), daughters of the Muse Melpomene and Achelous, women in the

upper parts of their bodies but bird below. It was their fate to live only so long as mortals who heard their

song failed to pass by. Ulysses, instructed by Circe, daughter of Sol [Helios], stopped up the ears of his

comrades with wax, had himself bound to the wooden mast, and thus sailed by."

Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 125 :

"He [Odysseus] had come to the island of Sicily to the sacred herds of Sol [Helios], but their flesh lowed

when his comrades cooked it in a brazen kettle. He had been warned by Tiresias and by Circe, too, not to touch

them, and as a result he lost many comrades there."

Ovid, Metamorphoses 14. 248 ff (trans. Melville) (Roman epic C1st B.C. to C1st A.D.)

:

"On Circe's shore we [Odysseus and his men] moored our one last ship but then, remembering Antiphates [the

Laistrygon] and savage Cyclops, we refused to leave the beach; but lots were drawn and I [Akhaimenides] was

chosen to approach those unknown halls. The lot sent me with shrewd Eurylochus and my true friend Polites, and

Elpenor, too fond of wine, and eighteen more of us to Circe's walls. As soon as we arrived and reached the

portal, lions, bears and wolves, hundreds of them together, rushed at us and filled our hearts with fear; but

fear we found was false; they meant no single scratch of harm. No, they were gentle and they wagged their tails

and fawned on us and followed us along, until the maids-in-waiting welcomed us and led us through the marble

vestibule into their mistress' presence. There she sat, in a fine chamber, on a stately throne, in purple robe

and cloak of woven gold; and in attendance Nymphae (Nymphs) and Nereides [i.e. sea-nymphs], whose nimble fingers

never comb a fleece nor spin a skein, but sort and set in baskets grasses and flowers, heaped in disarray, and

herbs of many hues; and as they work she guides and watches, knowing well the lore of every leaf, what blend is

best, and checks them closely as the plants are weighed. She saw us then and, salutations made, her welcome

seemed an answer to our prayers. At once she bade the servants mix a brew of roasted barley, honey and strong

wine and creamy curds, and then, to be disguised in the sweet taste, she poured her essences. We took the bowls

she handed (magic hands!). Our throats were dry and thirsty; we drank deep; and then the demon goddess lightly

laid her wand upon our hair, and instantly bristles (the shame of it! But I will tell) began to sprout; I could

no longer speak; my words were grunts, I grovelled to the ground. I felt my nose change to a tough wide snout,

my neck thicken and bulge. My hands that held the bowl just no made footprints on the floor. And with my friends

who suffered the same fate (such power have magic potions) I was shut into a sty. Eurylochus alone, we saw,

missed a swine's shape, for he alone refused the offered bowl, and, had he not escaped it, I should still be

numbered with that bristly herd today, for from his lips Ulixes [Odysseus] never would have learnt our ruin nor

ever come to Circe for revenge. He had been given by Cyllenius [Hermes], who brings the boon of peace, a flower

which the gods call moly, a white bloom with root of black. Secure with this and heaven's guiding grace, he

entered Circe's halls and as she coaxed him to the treacherous cup and with her wand was trying to stroke his

hair, he thrust her off and drew his sword, and back she shrank in dread. Then trust was pledged and hands were

clasped; she took him to her bed, and he, for wedding gift, called for his comrades' shape to be restored. So we

were sprinkled with the saving juice of some strange herb and on our heads he wand was touched reversed, and

words of countering power were chanted to unspell the chanted spells. The more she sang her charms, the more

erect we rose; our bristles fell; our cloven feet forsook their clefts; our shoulders, elbows, arms came back

again. Our captain was in tears, and we, in tears ourselves, with open arms embraced our lord, and the first

words we spoke, our very first, were words of gratitude. As year we lingered in that land, and much in that long

time I saw and much I heard; and this tale too which I learnt from one of the four acolytes who serve those

magic rites [Akhaimenides then relates the story of Kirke and Pikos (see section below).] . . . Much such tales

I heard and many sights I saw in a long year. Our idleness had made us slow and slack. Then the command came to

set sail again and put to sea. Titania [Circe] had spoken of vast journeyings, perplexing courses, perils of the

sea, the cruel sea, to face. I was afraid and having here found haven here I stayed."

Ovid, Fasti 4. 69 ff (trans.Boyle) (Roman poetry C1st B.C. to C1st A.D.) :

"The Neritian general [Odysseus] came [to Italy]: the Laestrygonians are proof, and the shore with Circe's

name [Circeii in coastal Latium]."

Propertius, Elegies 3. 12 (trans. Goold) (Roman elegy C1st B.C.) :

"He [Odysseus] fled from the bed of Aeaea's weeping queen [Kirke (Circe)]."

CIRCE'S CHILDREN & THE DEATH OF ODYSSEUS

Hesiod, Theogony 1011 ff (trans. Evelyn-White) (Greek epic C8th or C7th B.C.)

:

"And Kirke (Circe) the daughter of Helios, Hyperion's son, loved steadfast Odysseus and bare Agrios

(Agrius) and Latinos (Latinus) who was faultless and strong: also she brought forth Telegonos (Telegonus) by the

will of golden Aphrodite. And they ruled over the famous Tyrrhenians, very far off in a recess of the holy

islands."

Agias of Troezen, The Returns Fragment 4 (from Eustathius on Homer's Odyssey 1796.

45) (trans. Evelyn-White) (Greek epic C7th or 6th B.C.) :

"The Kolophonian (Colophonian) author of the Returns says that Telemakhos (Telemachus) afterwards

married Kirke (Circe), while Telegonos (Telegonus) the son of Kirke correspondingly married Penelope."

Eugammon of Cyrene, Telegony Frag 1 (from Proclus, Chrestomathia) (C6th B.C.)

:

"Telegonos (Telegonus), on learning his mistake, transports his father's body with Penelope and Telemakhos

(Telemachus) to his mother's island, where Kirke (Circe) makes them immortal, and Telegonos marries Penelope,

and Telemakhos Kirke."

Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca E7. 36 (trans. Aldrich) (Greek mythographer C2nd

A.D.) :

"When Telegonos (Telegonus) learned from Kirke (Circe) that he was Odysseus' son, he sailed out in search

of his father . . . He took the corpse [of Odysseus] and Penelope to Kirke, and there he married Penelope. Kirke

dispatched them both to the Islands of the Blest."

Pseudo-Plutarch, Greek & Roman Parallel Stories 41 (trans. Babbitt) (Greek

historican C2nd A.D.) :

"Telegonos (Telegonus), the son of Odysseus and Kirke (Circe), was sent [by his mother] to search for his

father, he was instructed to found a city where he should see farmers garlanded and dancing. When he had come to

a certain place in Italy . . . he founded a city, and . . . named it Priniston, which the Romans, by a slight

change, call Praeneste. So Aristokles ((Aristocles) relates in the third book of his Italian

History."

Ptolemy Hephaestion, New History Book 4 (summary from Photius, Myriobiblon 190)

(trans. Pearse) (Greek mythographer C1st to C2nd A.D.) :

"There is, he says, in the Tyrrhenian country a tower called Tower of the Sea, of the name of Sea [Greek

Thalassa ?], a Tyrrhenian poisoner; she worked for Kirke (Circe) and fled from her mistress. It was to her, says

the author, that Odysseus came [at the end of his life]; with the aid of her drugs, she changed him into a horse

and kept him with her until he died of old age. Thanks to this anecdote, the difficulty of the Homeric text is

resolved: ‘Then the sea will send you the softest of deaths.’"

Oppian, Halieutica 2. 497 ff (trans. Mair) (Greek poet C3rd A.D.) :

"That sting [of the sting-ray] it was which his mother Kirke (Circe), skilled in many drugs, gave of old to

Telegonos (Telegonus) for his long hilted spear, that he might array for his foes death from the sea. And he

beached his ship on the island that pastured goats; and he knew not that he was harrying the flocks of his own

father, and on his aged sire who came to the rescue, even on him whom he was seeking, he brought an evil fate.

There the cunning Odysseus, who had passed through countless woes of the sea in his laborious adventures, the

grievous Sting-ray slew with one blow."

Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 125 (trans. Grant) (Roman mythographer C2nd A.D.)

:

"She [Kirke (Circe)] herself lay with him [Odysseus], conceived, and bore two sons, Nausithous and

Telegonus."

Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 127 :

"Telegonus, son of Ulysses [Odysseus] and Circe, sent by his mother to find his father, by a storm was

carried to Ithaca . . . Telegonus with Telemachus and Penelope returned to his home on the island of Aeaea by

Minerva's [Athena's] instructions. They brought the body of Ulysses to Circe, and buried it there. By the advise

of Minerva again, Telegonus married Penelope, and Telemachus married Circe. From Circe and Telemachus Latinus

was born, who gave his name to the Latin language."

CIRCE WRATH : GLAUCUS & SCYLLA

Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 199 (trans. Grant) (Roman mythographer C2nd A.D.)

:

"Scylla, daughter of the River Crataeis, is said to have been a most beautiful maiden. Glaucus loved her,

but Circe, daughter of Sol [Helios], loved Glaucus. Since Scylla was accustomed to bathe in the sea, Circe,

daughter of Sol, out of jealousy poisoned the water with drugs, and when Scylla went down into it, dogs sprang

from her thighs, and she was made a monster. She avenged her injuries, for as Ulysses sailed by, she robbed him

of his companions."

Ovid, Metamorphoses 14. 1 ff (trans. Melville) (Roman epic C1st B.C. to C1st A.D.)

:

"[The sea-god Glaukos (Glaucus) wooed the nymph Skylla (Scylla) :] But Scylla fled. Enraged at his repulse,

he made in fury for the magic halls of Circe Titanis. And now the Euboian merman [Glaucus] through the main, the

main that held his heart, had left behind Aetne . . . the Cyclopes' fields . . . Zancle too behind and Regium's

facing bastions, and the strait, the ship-destroying strait, whose twin shores hem the bounds of Ausonia and

Sicula. Then on he swam with mighty strokes across the Tyrrhene Sea and reached the herb-clad hills and magic

halls of Circe, Sol's [Helios the Sun's] child, crowded with phantom beasts. He met her then and, mutual

greetings given, ‘Goddess,’ he said, ‘Have pity on a god, I beg of you. For you alone Titanis

can ease this love of mine, if only I am worthy. No one knows better than I the power of herbs, for I was

changed by herbs. And I would have you learn my passion's cause : on the Italian coast, facing Messenia's

battlements, I saw Scylla. I blush to tell my wooing words, my promises, my prayers--she scorned them all. But

you, let now your magic lips, if spells have aught of sovereignty, pronounce a spell, or if your herbs have

surer power, let herbs of proven virtue do their work and win. I crave no cure, nor want my wounds made well;

pain need not pass; but make her share my hell!’

But Circe (never heart more sensitive than hers to love's assault, whether the trait was in herself or Venus

[Aphrodite] might perhaps in anger at her father's [Helios the Sun's] gossiping have made her so) said :

‘You would better woo one who is willing, wants the same as you, is caught by love no less. You should be

wooed (How well you could have been!) and if you give some hope, believe me, wooed you well shall be! Trust in

those looks of yours; be bold and brave. See, I the daughter of shining Sol (the Sun), a goddess who possess the

magic powers of spell and herb, I, Circe, pray that I be yours, Spurn her who spurns you; welcome one who wants

you. By one act requite us both!’ But Glaucus answered : ‘Sooner shall green leaves grow in the sea

or seaweed on the hills that I shall change my love while Scylla lives.’

Rage filled the goddess' heart. She had no power nor wish to wound him (for she loved him well), so turned her

anger on the girl he chose. In fury at his scorn, she ground together her ill-famed herbs, her herbs of ghastly

juice, and, as she ground them, Carmina Hecateia [Circe] sang her demon spells. Then in a robe of deepest blue

went forth out of her palace, through the fawning throng of beasts, to Regium that looks across to Zancle's

cliffs. Over the raging waves she passed as if she stepped on solid ground, and skimmed dry-shod the surface of

the sea. There was a little bay, bent like a bow, a place of peace, where Scylla loved to laze, her refuge from

the rage of sea and sky, when in mid heaven the sun with strongest power shone from his zenith and the shade lay

least. Against her coming Circe had defiled this quiet bay with her deforming drugs, and after them had

sprinkled essences of noxious roots; then with her witch's lips had muttered thrice nine times a baffling maze

of magic incantations. Scylla came and waded in waist-deep, when round her lions she saw foul monstrous barking

beasts. At first, not dreaming they were part of her, she fled and thrust in fear the bullying brutes away. But

what she feared and fled, she fetched along, and looking for her thighs, her legs, her feet, found gaping jaws

instead like vile Cerberus. Poised on a pack of beasts! No legs! Below her midriff dogs, ringed in a raging row!

Glaucus her lover, wept and fled the embrace of Circe who had used too cruelly the power of her magic. Scylla

stayed there where she was and, when the first chance came to vent her rage and hate on Circe, robbed Ulixes

[Odysseus] of his comrades."

CIRCE LOVES : CALCHUS

Parthenius, Love Romances 12 (trans. Gaselee) (Greek mythographer C1st B.C.)

:

"The story of Kalkhos (Calchus) the Daunian [region in southern Italy] was greatly in love with Kirke

(Circe), the same to whom Odysseus came. He handed over to her his kingship over the Daunians, and employed all

possible blandishments to gain her love; but she felt a passion for Odysseus, who was then with her, and loathed

Kalkhos and forbade him to land on her island. However, he would not stop coming, and could talk of nothing but

Kirke, and she, being extremely angry with him, laid a snare for him and had no sooner invited him into her

palace but she set before him a table covered with all manner of dainties. But the meats were full of magical

drugs, and as soon as Kalkhos had eaten of them, he was stricken mad, and she drove him into the pig-styles.

After a certain time, however, the Daunians' army landed on the island to look for Kalkhos; and she then

released him from the enchantment, first binding him by oath that he would never set foot on the island again,

either to woo her or for any other purpose."

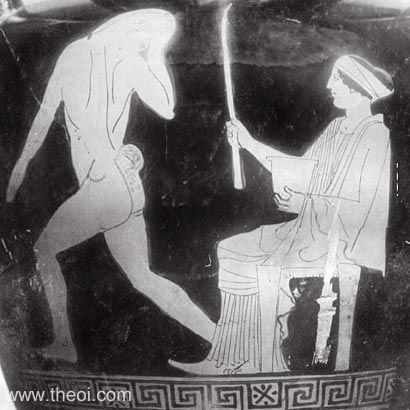

CIRCE LOVES : PICUS

Ovid, Metamorphoses 14. 308 ff (trans. Melville) (Roman epic C1st B.C. to C1st A.D.)

:

"A year we [Odysseus' men] lingered in that land [Kirke (Circe)], and much in that long time I saw and much

I heard; and this tale too which I learnt privately from one of the four acolytes (famulae) who serve those

magic rites. She pointed out to me, one day, while Circe dallied with my lord [Odysseus], a statue of a youth,

in snow-white marble, set in a shrine and gaily garlanded with many a wreath, who bore upon his head a

woodpecker. I asked her who he was, why worshipped in that shrine, and why the bird upon his said, for I was

curious. ‘Listen,’ she said, ‘and learn from this tale too my mistress' magic power and mark

my words. King Picus, son of Saturnus [Kronos (Cronus)], ruled the land of Ausonia [Latium], a king whose chief

delight was chargers for battle. You observe his features. Gaze upon his striking grace and from his likeness

here admire the truth . . . Many a glance he drew from Dryades born among the Latin hills; he was the darling of

the Numina Fontana (Fountain-Sprites) and all the Naides (Naiads) of Albulba and Anio and Almo's streams . . .

[but he loved only Canens, daughter of Janus, and wed her.]

‘Once, as her [Canens] soaring voice poured out its song, Picus left home to hunt the boars that roamed

his countryside. He rode a prancing bay, carried a pair of spears, and wore a cloak of purple with a clasp of

tawny gold. To those same woods [Kirke (Circe)] the daughter of Sol (the Sun) [Helios] had also come from that

Circaean isle named after her, to search the fertile hills for her strange herbs. Unseen in the undergrowth she

saw the young king--saw, and gazed entranced. The herbs fell from her hands. Like blazing fire a thrill of

ecstasy raced through her veins. Then, gathering her smouldering wits, she meant to bare her heart, but could

not come to him, he rode so fast, so close his retinue. "You'll not escape," she cried, "No!

though the wind whirl you away, if I still know myself, if still my spells their magic power retain, nor all the

virtue of my herbs is vain." She summoned up a spectre of a boar, a phantom boar, and made it race across

before his eyes, and dart, or seem to dart, into a spinney where the trees stood close and crowded so no horse

could penetrate. Off in a trice, unconscious of the trick, sped Picus to purse his shadowy prey, and, leaping

nimbly from his foam-flecked horse, fumbled on foot to follow his false hope and soon had wandered deep into the

wood. Then Circe turned to prayers and incantations, and unknown chants to worship unknown gods, chants which

she used to eclipse Luna's (the Moon's) [Selene's] pale face and veil her father's [Helios the Sun's] orb in

thirsty clouds. Now too the heavens are darkened as she sings; the earth breathes vapours; blind along the

trails the courtiers grope; the king has lost his guards; the time and place are hers. "Oh, by your eyes,

those eyes of yours," she said, "that captured mine, and by your beauty, loveliest of kings, that

makes me here, a goddess, kneel to you, favour my passion, and accept as yours my father, who sees all, Sol the

Sun above, and harden not your heart to Circe Titanis' love."

‘But fiercely he repulsed her and her plea. "Be who you may," he cried, "I am not yours.

Another holds my heart and many a year I pray shall hold it. Never will I wound for any stranger's love my

loyalty, while fate keep my Canens Janigena safe for me!" Time after time she pleaded--all in vain.

"You'll pay for this," she said, "never again shall Canens have you home. Now you shall know what

one who's wronged, who loves, who's woman too--and I that loving woman wronged--can do!" Then eastwards

twice and westwards twice she turned, thrice sang a spell, thrice touched him with her wand. He fled and

marvelled that he ran so fast--so strangely fast--then saw he'd sprouted wings! Outraged to find himself so

suddenly a weird new bird in his own woodland glade, he pecked the rough-barked oaks with his hard beak and

wounded angrily the spreading boughs. His wings assumed the purple of his cloak, the golden broach that pinned

his robe became a golden band of feathers round his throat and naught was left of Picus but his name [i.e.

picus is the Latin word for woodpecker]. Meanwhile his courtiers through the countryside were calling

him and calling, but in vain. Picus was nowhere to be found. Instead they chanced on Circe (who by now had

cleared the air and let the wind and sun disperse the mists) and charged her, rightly, with her guilt and

claimed their king and threatened force and aimed their angry spears. She sprinkled round about her evil drugs

and poisonous essences, and out of Erebos and Chaos called Nox (Night) and the Gods of Night (Di

Noties) and poured a prayer with long-drawn wailing cries to Hecate. The woods (wonder of wonders!) leapt

away, a groan came from the ground, the bushes blanched, the spattered sward was soaked with gouts of blood,

stones brayed and bellowed, dogs began to bark, black snakes swarmed on the soil and ghostly shapes of silent

spirits floated through the air. Stunned by such magic sorcery, the group of courtiers stood aghast; and as they

gazed, she touched their faces with her poisoned wand, and at its touch each took the magic form of some wild

beast; none kept his proper shape. The setting sun had bathed Tartesus's shore, and [the wife of Picus] Canens'

watching eyes and heart in vain had waited for her husband. Through the woods her household and the townspeople

had spread with torches in their hands to meet their lord. Nor was the Nympha content to tear her hair and weep

and wail (all that she did); out like a madwoman she rushed herself and roamed the countryside of Latium . . .

[and eventually wasted away in her mourning.]’"

Virgil, Aeneid 7. 187 ff (trans. Day-Lewis) (Roman epic C1st B.C.) :

"[Depicted on the doors of the palace of the king of Latium :] There, holding the augur's staff, arrayed in

a short toga purple-striped, the holy shield on his left arm, sat Picus, tamer of horses: vainly lusting to bed

with him, golden Circe had used her wand and her magic potions, and turned him into a bird, into a pied

woodpecker."

CIRCE & HER SON FAUNUS

The Italian god Faunus was sometimes described as a son of Kirke (Circe) by the god Poseidon.

Nonnus, Dionysiaca 13. 327 ff (trans. Rouse) (Greek epic C5th A.D.) :

"Phaunos (Faunus) came [to join Dionysos in his war against the Indians], leaving the firesealed Pelorian

plain of three-peak Sikelia (Sicily) the rocky, whom Kirke ((Circe) bore embraced by Kronion (Cronion) of the

Deep [Poseidon], Kirke the witch of many poisons, Aietas's (Aeetes') sister, who dwelt in the deep-shadowed

cells of a rocky palace."

Nonnus, Dionysiaca 37. 10 ff :

"Phaunos (Faunus) who was well practised in the secrets of the lonely thickets which he knew so well, for

he had learnt about the highland haunts of Kirke (Circe) his mother."

Nonnus, Dionysiaca 37. 56 ff :

"Phaunos (Faunus) the son of rock-loving Kirke (Circe), the frequenter of the wilderness, who dwelt in the

Tyrsenian land, who had learnt as a boy the works of his wild mother."

CIRCE INVENTRESS OF MAGIC & SPELLS

Kirke (Circe) was sometimes regarded as the inventress of magic and spells. In the Homeric Epigram (below) she is invoked almost as the daimona (spirit) of magic.

Homer's Epigrams 14 (trans. Shewring) (Greek epic C8th B.C.) :

"[Invocation to Kirke (Circe) :] Daughter of Helios, Kirke the witch (polypharmake), come cast

cruel spells; hurt both these men and their handiwork."

Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 4. 45. 1 (trans. Oldfather) (Greek historian

C1st B.C.) :

"[A late greek rationalisation of the Kirke (Circe) myth :] She [Hekate (Hecate, daughter of Perses the

brother of Aeetes] married Aeetes and bore two daughters, Kirke (Circe) and Medea, and a son Aigialeus. Although

Kirke also, it is said devoted herself to the devising of all kinds of drugs and discovered roots of all manner

of natures and potencies such as are difficult to credit, yet, notwithstanding that she was taught by her mother

Hekate about not a few drugs, she discovered by her own study a far greater number, so that she left to the

other woman no superiority whatever in the matter of devising uses of drugs. She was given in marriage to the

king of the Sarmatians, whom some call Skythians (Scythians), and first she poisoned her husband and after that,

succeeding to the throne, she committed many cruel and violent acts against her subjects. For this reason she

was deposed from her throne and, according to some writers of myths, fled to the ocean, where she seized a

desert island, and there established herself with the women who had fled with her, though according to some

historians she left the Pontos and settled in Italia on a promontory which to this day bears after her the name

Kirkaion (Circaeum)."

Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 4. 50. 6 :

"[Medea] said [to the Argonauts] that she had brought with her many drugs of marvellous potency which had

been discovered by her mother Hekate (Hecate) and by her sister Kirke (Circe); and though before this time she

had never used them to destroy human beings, on this occasion she would be means of them easily wreak vengeance

upon men who were deserving of punishment."

Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 4. 54. 5 :

"[Medea] entered the palace [of King Kreon (Creon) of Korinthos (Corinth)] by night, having altered her

appearance by means of drugs, and set fire to the building by applying to it a little root which had been

discovered by her sister Kirke (Circe) and had the property that when once it was kindled it was hard to put

out."

Statius, Thebaid 4. 536 ff (trans. Mozley) (Roman epic C1st A.D.) :

"She [the seeress Manto] obeys, and weaves the charm wherewith she disperses the Shades and calls them back